Today, NaNoWriMo sent me an email titled, “How to go on an adventure without leaving your home.” They sent me the email because, a number of years ago, I signed up at the site — where every November writers of all ages log on as they each try to write, and complete, the first draft of a novel or other 50,000 word project. I have many started projects on the site, but no finished ones. Still, that doesn’t stop me from getting excited about starting again when November rolls around, for somehow writing a novel with the incentives of fun badges and word-count stats is so much more fun than toiling on one’s own. (You can create your own personal challenges even at other times of the year, and in April, they’ve got Camp Nanowrimo. Just in time for Poetic Earth Month, too!)

Books, whether you are (attempting to) write them, or reading them, are a kind of travel you can do for free, from right where you are. But recently I’ve had trouble finding the inspiration to do either, though reading and writing (fiction) have been my most passionate hobbies for, literally, ever. Ever since I could make letters I was making fake little books. And, as one of the things I’d meant to do on Poetic Earth Month (the site, not the month — which, as I discovered, can turn into the amazingly apt acronym PoEM) was review children’s picture books, and as I am not leaving the house right now, I went through the stack from when I was little and ended up with a huge pile that, I felt, had some relevance to thoughts about sustainability and earth care.

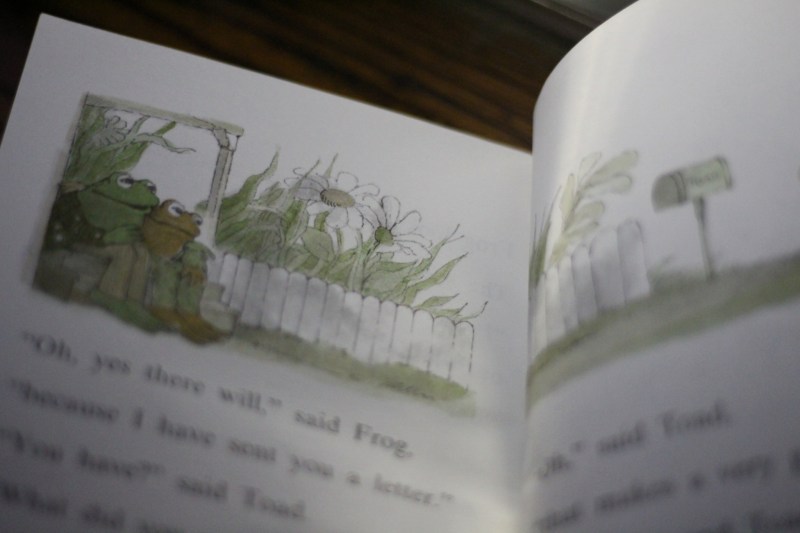

Frog and Toad Are Friends, written and illustrated by Arnold Lobel, does not, perhaps, have such a direct association to the ecological as some. But interactions between the characters and the environment are integral to all the Frog and Toad books, and it felt timely: the first story in the book, “Spring,” takes place in April. Yes, I must admit: this is a learn-to-read book, a genre that I hate with a passion, no surprise as I still have memories of slogging through some of the most banal stories, paired with the most disturbing illustrations, that book-writing grownups ever cooked up to torment children with.

The Frog and Toad series is one of a few shining exceptions to the rule; it’s a group of stories that I remember fondly, and re-read every so often, even now. The premise that makes these books work so well? They actually tell stories. Without dumbing down the themes or the plots or even the dialogue, while still keeping each one simple and distinct. Frog and Toad Are Friends won the Caldecott Honor Award for a reason! And the friendship between Frog and Toad, with Frog always ready to go on an adventure, Toad a little more cynical, but each willing to help each other out, still makes me smile.

In the first story in this volume, “Spring,” Frog wants to spend time with Toad and enjoy spring; Toad wants to sleep.

“You have been asleep since November,” Frog says, (perhaps Toad was all tired out from having written a novel) and Toad replies, “Well then, a little more sleep will not hurt me. Come back again and wake me up at about half past May.” This is just one example of the intelligent humor in the series that recognizes the fact that just because kids can’t read very well doesn’t mean they can’t think. In fact, the way Frog solves the problem of Toad not wanting to get up yet is so clever that I will refrain from pointing it out here, as I don’t want to spoil it.

It’s a little funny to call on a picture book as an example of the practice of mindfulness; but I don’t think it’s that much of a stretch — at least not for this collection. Picture books skip past the deluge of information and terrible news that is always ready to spring out at us whenever we open up a computer, or look at our phones; and they condense the sometimes complicated and emotionally exhausting sagas of fiction into something much simpler, while not being any less profound. Indeed, I’ve cried at the end of far more picture books than ever any fiction.

It might be tempting to hole up inside the house, as Toad did. Whether it’s because you’re just tired, or because the world outside seems to only have sad things to offer.

As Frog tells Toad, “The sun is shining! The snow is melting! Wake up!” Toad, in his dark house, with all the shutters closed, says, “I’m not here.”

When Frog tells Toad all the things they can do this year, from running and swimming to counting the stars, Toad says he’s too tired to do that and wants to go back to bed.

I think this is a sentiment that everyone can relate to, at one time or another. But what this collection of stories persuasively shows is that spending time in nature, especially with a friend, is not tiring at all. In fact, it’s rejuvenating: and there’s no argument necessary. Just looking at the book, experiencing it, is rejuvenating. Science has even proven (if we needed proof to tell us our gut instincts were right) that green spaces allow you to experience the world in a different way, a way that decreases your stress, and calms you down.

Even something as simple as sitting on your front porch, like Frog and Toad, and looking out.

The stories in Frog and Toad Are Friends are funny, thoughtful, clever, and include themes useful to people of any age — without being morality tales. And the illustrations that accompany them, done in soft greens, browns, and yellows, are always surprising and peaceful. They create a sense of scale (Frog and Toad are quite small, of course, and frequently walk through comparatively larger plants and interact with other animals, like birds, snakes and turtles); they draw attention to the important pieces of the action; and they add to the whimsical mood. Without the pictures, the stories would not be what they are. Thus, the collection passes the test that, to me, seems to divide the great picture books of the world from all the rest.

If the Frog and Toad books reflect on the earth, and the way we ought to take note of it (but many times forget to), it is in the pictures: natural scenes in meadows and woods and streams, featuring detailed and lively depictions of animals and plants that seems to acknowledge the life in all of them. And it is in the words, too: in the emphasis the stories put on small acts, of freely caring for those with whom you live in the world.