note: all featured images are from the public domain

***

Noticing

“At this rate, there will be nothing else to watch in twelve years.”

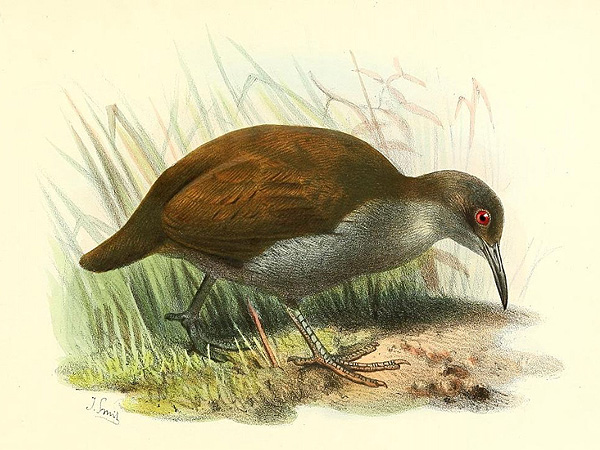

For as long as they can recall, the watchers have taken note of what happens to the world, recording everything in weighty scrolls as large in diameter as the equator. They know every weather pattern and every invention of Man. Because there are many things to look upon, they specialize: Shift watches birds. Cormorant, pelican, buzzard and dove. Macaw, toucan, peacock. Around the table with its cloth made of spun clouds, Shift watches the swirls and eddies as the lower, trailing end of the pristine fabric trails on the rough floor. It has gone grey at the tips. And every time they meet these days, the grey has traveled higher.

They leave the table when the meeting is over.

“What can we be if we’re not watchers?” Brook says. “Am I supposed to only categorize and re-read what has already been?”

No one answers.

Outside the dwindling hall, Shift sees Trace standing with their back to the archway. In the noon sun, they are only a pattern of brightness and shadow, as though something in them, standing against the inevitable, has fissured.

They walk by, Brook and Shift, and as they do Shift catches the emptiness in Trace’s gaze and shivers. “Come to the records room with us?” they ask on a sudden whim.

Trace turns their head, blinking free and seeming somewhat surprised to see Shift standing there. “No, you two go on ahead,” they say pleasantly. They walk away.

Next time the watchers meet, Trace is gone. They have pulled themselves apart. And they are not the only one to do so. The endless hall is half-empty, and it echoes with the spaces others should be. It is the first time Shift has seen the same destruction that is in the world echoed here, and when they leave the gathering, they falter.

“You won’t do that, Brook,” Shift says.

“Of course not,” Brook says. “I don’t think I’ll show up again though. It’s too awful, seeing…” they fall silent. “Anyway. You know where to find me, in my section of Noticing. There’s an awful lot to replay.” They smile wanly and walk off, waving, swallowed in the endless corridors.

For a moment Shift is alone. Then they pace to the canyon between here and the world, looking down. Below, sky. Below the atmosphere and space, inside the everything that makes up matter. Shift thinks about standing here and watching for twelve more years until there is nothing left but a void, a dark chasm to be stopped up. And they can’t.

They take out a needle, and coax the thin cloudlets from the stream between here and the world. Floating pearl, it drifts as they twirl it between their fingers, into something thin and strong. They turn it to thread, and sew a form made of afternoon sunlight. It is a diver, wings bent down, and when they step inside it they fall toward the sea.

***

Shift coughs up water, and blinks. The ground has risen up to meet them, and their perfect form has gotten twisted around. The wings are broken, they think. Something else is wrong with the beak and eyes. They need to walk, but they don’t have the right ability to do so; outside the range of their vision Shift can hear a human saying something, over and over again. “It’s hurt!” A low, distressed voice. “It’s hurt.” They look up when the speaker takes them in its hands, carefully, as though cradling their fragile self and smoothing down the spaces where the cloud-thread has broken. A male of the species, with blue eyes. Shift looks into them, wondering how the sky has been captured in a glass, and piece their form together from pain and the speaker’s words. It has a mouth this time and it is human like their rescuer. They become too cumbersome to carry and are set down, but the speaker doesn’t stop holding their broken wing, broken shoulder, broken hand.

***

“It was touch and go for a while,” says the blue-eyed man.

Shift groans, sitting up and looking over their—his?—new body. It looks akin to their rescuer. Shift feels unsettled. They have never been interested in Man, and less so since they found out that there would be nothing left in twelve years, and Trace died and the infinite hall emptied.

They tell the man this.

“Oh,” says the man.

“Oh?” Shift says. “Is that all?” They are feeling angry, a roiling anger like a storm. This species is destroying everything and this man, who rescued Shift, has nothing to say about it but oh.

“I thought you were human,” the man says.

“You rescued a bird,” Shift says. Their voice starts off confident but by the time they finish speaking, their voice has trailed off into uncertainty. “Didn’t you?”

The man rubs a hand through his dark hair, and Shift watches the deepness of shadows in it. It is the right color for feathers, this man who is not a bird. “I thought I did,” the man admits at last. “But by the time you were here you, well… and I thought maybe I just imagined it. That I was so worried… pieces were warping and I had to think you into being somehow. I think. I’ve heard of things like that, you know? Magical containers for essence. That’s what all bodies are, I suppose. I never thought it was real, but I remembered quilting when I was a kid. My mother would tell me fairy tales when—”

“Why are you telling me this?” Shift asks abruptly, and the man stops speaking.

“I don’t know,” he says. “Sorry. Uh. You can go in the bathroom if you want. If you think you still need help I can try to call a doctor. I don’t know if I can find one, but…”

Shift navigates the room. It is a small, two-bed room with the lights turned down. On one rickety bedside table is a pocket sewing kit with scissors that have fallen apart and thin pink and orange polyester thread on small black plastic spools. The whole thing feels cheap and off-kilter, and when Shift enters the bathroom they turn on the light and flinch at the electric buzz. They close the door behind them, legs shaking, and slide to the floor. They have not seen anything yet. They still feel deflated, and they hate their weak human arms.

Salt-water leaks from their open eyes, as though they are losing the rest of the sea.

“Are you…okay?” a hesitant voice says through the door. It’s the blue-eyed man. Shift draws an arm roughly across their face.

“Yes,” they say. They stand up, to more fully convince themself, and stagger to the mirror. The human looking back looks much like the blue-eyed man. Hair just the right color for feathers. Shift watches the way the air eddies around it. They have clear blue eyes that are puffed red from crying. They look ordinary dressed in a large t-shirt and a red sweater. What an ordinary man they are.

Underneath their shirt the spot where their wings had broken and the place where their guts had been falling out and the knobbled knees are sewn up with pink and orange thread. Shift brushes a hand across the spot and hisses at the sudden ache of pain. Their fingers come away tipped with blood.

***

“So,” says Mikhail.

Shift is walking around the small room, close to the window, looking at the blacktop outside. Through the dull glass and the cross-pieces of the shades, it could be nothing but a piece put in a box.

“Twelve years.”

“Less, for you,” Shift says. “That’s just when there will be nothing left to watch at all.” They shrug. “For you, it will be more like five.”

“And for you I guess,” Mikhail says. Shift clenches their fists and watches the skin grow taut under the tension of their anger.

“Yes,” Shift says at last. “And for me.”

“Is there something you want to do? Before the end?”

Shift shrugs, lowering themself onto the white metal heater. The cold air of the window behind them and the scratching of the thread in the wounds where their wings have been make them grimace. They dig their fingers into the grating, and the soft heat blows upward, drying the tear-tracks on their face. “What about you?” they say.

Mikhail laughs. “Up until yesterday, I was heading for the border.”

Shift squints at him.

“To get out of the draft,” Mikhail explains, in a quieter voice. He looks away. “I left my country because I didn’t want to be killed in the airship battle. It’s not that I don’t want to… fight. I just don’t know what the point is of destroying one of the last habitable cities on earth under the illusion of gaining more ground.”

“And you aren’t heading for the border anymore?” Shift asks.

“Got across it. Cost me the rest of my money. And now I’m free in no man’s land. Outside all the pressure-domes and the hydroponic gardens. I’m hardly going to live for more than six years in the Wastes, considering the pollution. So. One year less isn’t bad I guess.”

“Isn’t bad I guess,” Shift echoes. “I was hoping for one lifetime,” they admit. They remember their beak piercing the sky as they fell.

“Why not stay where you were?” Mikhail says.

“I don’t know,” Shift admits, in a whisper just touching the back of their throat. “It seemed… inconceivable.”

“We have one more night here,” Mikhail says at last. “You should rest.”

“I wish I could,” Shift says.

The heater is still working, and yet they shiver.

***

The Roman roads are straight and still standing. This is what shows the way into the Wastes beyond every limit. Mikhail has a backpack with his remaining possessions. Shift has the clothes on their back that were once Mikhail’s.

The Labrador duck once spent its winters in the shelter of inlets, feeding on mollusks. The males with striking black and white, females with soft brown plumage. It didn’t know how to live outside the habitat of its short migrations, and now the only thing that’s left is stuffed specimens in museums.

This is what Shift tells him that first day as they walk. They have a pair of ratty sneakers that Mikhail bartered for, because the blue-eyed man had brought with him only one pair of boots. Inside the sneakers, their feet are wrapped in rags. Shift can feel blisters raising, and they look ahead, arms swinging at their sides. The pall of low smoke hasn’t left since midday, and the sunset is going to be brilliant.

“One time a man went fishing in the choppy waters,” Mikhail says. “This was long ago, you remember. And he saw a woman swimming as though she were flying, like she belonged there. And a seal-skin lying on the ground. He took the skin and hid it, and then convinced her to come back with him, where they lived a long and happy life. But one day she found the skin again, in the bottom of a trunk, and took it and left him and their children behind, and jumped back into the waves.”

“That never happened,” Shift says.

“That’s the story the way my mother told it,” Mikhail replies, with a shrug. “Maybe the same thing happened to your duck. Maybe it got tired of living stuck in one place while everything fell down around it.”

“And maybe it just died.”

They walk in silence until the light glances off the standing stones and everything else is bathed in shadow; then they sit. The bloody edge of the grass seems to shimmer. Shift pulls the shoes from their feet, and their needle from their sleeve. They pull the grass free, all cellulose and refracted light and deep reaching roots in what remains of dust. They stitch the sides of their feet, building calluses out of the stubborn things and slip-stitching it into skin. They put the needle away.

Mikhail watches. “I’ve never seen real magic before,” he says, as Shift rubs their toes and arches until the stitches sink under their skin.

“There’s no such thing as real magic,” Shift says. They push and push, but the ache doesn’t leave their sinews and bones. One crooked toe, with a ripped nail, bleeds sluggish and dark.

***

The New Caledonian rail slipped from sight quietly, making its way up the mountains to escape from feral dogs and pigs. Brown with a grey belly and a yellowish bill, it lived in the spaces when sunlight disappeared, twilight or perhaps night.

Shift knows its sound, they had recorded it as they watched, but now that is lost to them, stuck in their section of Noticing. They cannot reproduce it for Mikhail, where they sit curled up around a small fire in a hollow under the stars.

“It’s okay,” Mikhail says. He takes their shaking hand, brushing his fingers across their palm. “I believe you. Just tell me the rest.”

“You don’t understand,” Shift says. “If I hadn’t recorded it there would be nothing left. And there’s twelve years left before the end, but I left, when I could have saved others.”

“But you wouldn’t have saved them,” Mikhail says quietly. “Not really. You would have written about them, put them in a library no one visited while your own species committed suicide. And when the universe was empty, what would it matter that you’d found the last bird in the world?”

“You sound very heartless, Mikhail,” Shift says.

“I’m realistic,” Mikhail says.

“That is how you convince yourself you don’t care,” Shift says, and turns away.

A hollow, eerie wail throws itself around the stones, the old music of the wind.

“I’m sorry,” Mikhail says.

“But you do care,” Shift says. They look between the angles of their legs, covered in worn denim. “You saved me. You saw me when I was wounded, and it mattered to you. How can I care any less about what I see?”

“Why not stay, then?” Mikhail says. “Stay and do your duty. Keep everything close.”

“Because I couldn’t,” Shift says, and their heart aches. They press their hands to it, as though fearing for more blood, but there is nothing but long, inward breath. “I couldn’t watch it all disappear.”

They press their eyelids shut, until all they can do is feel.

***

They cross paths with a band near noon. The Men give them suspicious looks and herd them away from the food wagon. When Mikhail asks about the lay of the land they say, “it’s all Wastes from here on out,” and laugh.

Mikhail nods and they leave quietly while Shift looks behind at the hard, stained faces and wary eyes.

They walk in silence until the band is out of sight and sound.

“There’s safety in numbers,” Shift says.

“And competition,” Mikhail says. “Surely you know about that.”

Shift shrugs. “I don’t understand Men,” they say.

“Nobody does, I think,” Mikhail says. Mikhail has one hand curled around his backpack strap, worrying at the plastic, and he’s looking forward when the shots fire. Shift stumbles, and watches the smoke ring its way through the blue-eyed man’s shoulder. Mikhail gasps and falls, looking almost surprised, and the Men approach from all side, eyes on his pack.

Shift grits their teeth and feels something white-hot, stumbling to their feet. At first the Men don’t seem to notice; and if they did, what would they care, about an ordinary man swaying on his feet? Shift can’t move, can’t summon up the strength to walk over, and they see the group bend over Mikhail. They need to act, before the pack is stolen, before Mikhail is killed, but they can’t take a step. So they bend their arm; move the t-shirt up and rip the stitches free, sticking their arm inside the hole in their belly, dipping their fingers into the slippery surface of their intestines as blood sluices its way around their elbow, until they have reached just deep enough. And then they pull, and the shadows come out, something utterly too big for the world, something that is meant to remain in the place beyond. They close their eyes and scream. They are crawling out of the skin, and dragging it along behind them like a backpack full of meat. They reach the Men at the same time and slice clean through each throat, six at once, and watch the blood arc its way sizzling onto the ground.

Then Shift is falling, eyes open onto a greyed sky, hand pressed to their stomach, and hurting. Something in their lungs rattles.

“Shift?” Mikhail says. He reaches out. “Shift, look, you can’t die on me. Not yet. Five more years, you said, remember?”

Shift chokes. Bubbles crawl up their throat. “I… remember.”

They take their needle between slippery fingers and make a shaky running stitch across the wound, using blood and the sharp tang of effluent and five more years, you promised.

They think they’ve figured out how to breathe; they zigzag fear around the hole in their lungs, pushing the silver needle through until it’s closed.

They sit up. Sweat is running over their face, their blood-covered stubble. Their shoulders are tensed and a line of blood is running between their shoulderblades where the gashes from their wings have opened up again.

“We can’t stay here,” Mikhail says. His face is drawn, and he has a hand pressed to his shoulder. Blood drips between his fingers. Together, they stand.

“The wagon,” Shift says.

Mikhail nods, and they make their way back.

There are three men left where the band had been. Three men looking bored and waiting around, not knowing their companions have been killed.

“We’ll never get them all,” Mikhail says.

“Yes,” Shift says, voice hard. “We will.” They open their hand for the gun that shot Mikhail.

“Do you know how to use that?” Mikhail whispers.

“No,” Shift says. “But it can’t be that hard.”

Mikhail shakes his head. Propping his injured arm against his chest, he aims, and three men fall in the space between three heartbeats.

“I thought you weren’t a soldier,” Shift says, quietly.

Mikhail shoves the gun into his open pack. He walks to the wagon, and searches for something to patch himself up.

Later, they sit on the end of the wagon.

Pallas’s cormorant used to live across the reaches of the globe, but it’s been a long time since then. They are huge, and stand watch on the cliff’s edge. Black-winged, green-backed, they avoid flight, and are overrun by men wanting feathers, whales, food, furs. It is not a battle. It is a slow massacre.

Shift tells Mikhail this in rambling loops of speech while Mikhail cries beside them.

“Are you okay,” Shift says, interrupting their description of the skeptical look in the seabird’s yellow-ringed eyes.

“I’ll be fine,” Mikhail says. He reaches out his hand and Shift takes it tightly within theirs. Shift raises the hand to their lips and kisses like they could stitch together the hurt. They press their lips to the back of Mikhail’s wrist. They kiss like they must never stop touching or they will fall apart.

“I should have known,” Shift said. “I should have suspected them when I saw.”

“I’m the one who almost got us killed,” Mikhail says, “because I wanted to speak to them instead of walking by.”

“I guess we both made a mistake,” Shift says at last. They pause. “At least we have a wagon now.”

Mikhail laughs raggedly, a burst of something that shakes his entire frame, and pulls Shift close.

***

The wagon is a burden. It carries much inside it but it slows their progress to a long rattle that traces ruts of dust in their wake. The only time Shift really likes it is at night, when they stop moving, and curl up inside. The bow-curve of its edges frames the night sky, which is more and more an endless pool of shimmering light, geode-sharp, the further they get into the Wastes. Mikhail tells them about the constellations; Shift looks at the bright points of Seth, murderer of Osiris, being held back by Tawaret; and they feel themself flying with the Geese of Ra as though to follow the spiraling path up, through the edge of the chasm and back to the place beyond the world.

Beyond the ridge of their spine, in the spaces on either side, Mikhail slides his palms along the knotted scars done up in pink and orange thread. “I’m not very good at this,” he says quietly, scraping a fingernail against the rolled surface. “When you heal yourself it’s like nothing ever happened but this…”

Shift shrugs. “I wouldn’t have been able to,” they say. “I was dying.”

“And now?”

“Like you said, Mikhail,” Shift whispers. “You put magic into it. You had to think me into being. I could not get rid of it without taking my body apart, until there was nothing left underneath.”

“And if you did,” Mikhail says. “Would you be able to go back?”

“I don’t think so,” Shift says. “Gravity is too strong, you know. And I think…” they fall silent, and feel the impression of heat from Mikhail’s chest. With their face turned away they can fall apart soundlessly, and if Mikhail notices he says nothing. Just waits, and breathes. “I’ve forgotten how I crafted my wings.”

***

A flock of passenger pigeons numbered billions, once. Reddish brown, such an unobtrusive color, but the iridescence on the neck and mantle: bronze, violet, green; slate and olive; grey-blue, pink tail, coral feet. Poised and slender, fast and nomadic, with pointed wings; scapula and sternum, and the sound! Raucous cacophonous, kek-kek, kee-kee-kee-kee, keeho! How loud the skies were, once! The noon was blotted out to endless darkness, the wings buzzed, and when they moved into a smaller surface, oh how like a dragon, a twisting blizzard, a column of unimaginable depth!

Shift had watched, once, for fourteen hours a flock pass by, and Noted it. It had been, they thought, as endless and joyous as the watchers. They traveled endless forests, their weight bending structures and creating it as they lived, until the forests ended, until they were hunted for food and sport. Until the last remnants were gathered where last things always are; prized beyond measure because they are gone.

Some photographs of the captives remain. They watch, still living, though in monochrome; a single speck of what had once been the most numerous bird species in the world.

***

Some nights Mikhail takes the fabric scraps scavenged from the dead they left behind and washed clean in the frozen marshes, and he sews. With a tiny needle like a flash of starlight, in and out of the remains of wool flannel. A red piece is emerging, with a zigzag of blue cuffs tracing below the sky. He outlines the birds Shift tells him about in orange and pink against a rubicund surface, filling the blank canvas with life.

“The Uprising happened when I was younger,” Mikhail says, squinting by the light of the small grass-fed fire. “For three years I lived with my brothers going from house to house, while every day another pressurized dome shattered. I didn’t know what it was about then. I didn’t know what anyone was fighting for. All I knew was the way the sky looked when it was broken; like this…” he traced a jagged, teethlike structure in front of him. “Dark in front, and even darker behind it, terrifyingly so. Then there were talks of hostages and negotiations and everyone thought maybe this time. You know? But we didn’t stop. The cities, I mean, and the machines running them.”

“I remember,” Shift says. “I counted the seventeen last birds in that year alone.”

“And for you?” Mikhail says. “What was it like up there? What is it like? I suppose you never had a childhood, but you have a history, and that means something.”

“We had no history,” Shift says. “We had yours. Everything you ever did in this world we counted and put meaning to.”

“There you go then,” Mikhail says. “If you put meaning to it, you made it yours. What stories did you tell about us?”

“Why should we need one? The world keeps going, until it doesn’t,” Shift says. “And when it doesn’t, then we lost all our stories. How are we supposed to live with that?”

Mikhail says nothing. He sews, and the sharp point of his needle pierces the fabric, giving it strength, changing it utterly.

Shift continues. “We had a meeting hall made of clouds, endless and infinite. Outside it, we watched. I saw how things were and are; how the first stirrings of uncertainty traveled like the gulf stream. Nothing was untouched. We lost our moorings as what we watched slipped away beneath us. Then the infinite became less. Some pulled themselves apart, becoming nothing. I… bounded myself to this.” Shift watches, entranced by flame and Mikhail’s eyes, storm-dark. The small, fragile thread pulls upward, the cloth upon his knee framed by his hands.

“Sometimes I wish I’d stayed,” Mikhail says, softly. “I cast myself out when I left; I became nothing but a wasteland scavenger untouched by humanity. And all because I didn’t care enough. Or perhaps because I was afraid.”

“And how was fighting airship battles supposed to save the world,” Shift says. They put their chin in their laced fingers, and feel the brush of their ankle against Mikhail’s skin.

“I don’t know,” Mikhail says.

***

Shift takes stone and the sound of the wind wailing and chain stitches it along their arms, when they finally rest, tired from dragging the wagon endlessly behind them. They feel more human than they ever have, something like an ordinary man. Their hands are rough and their lips cracked from the wind and cold, when they and Mikhail find a deep hollow in the mountains. They stop moving while the snow blows in, and Shift feels nothing like a bird at all.

The pot pot chee’s wings were brilliant emerald, fading to turquoise; with a yellow and orange head. It thrived in swamps and rivers in ancient forests, and of all parrots had the northernmost range. They ate toxic seeds and so they too, were toxic. The forests were eaten away, and those that returned to their dead and dying kin were killed. But the final disappearance of the species, over hardly a decade, and what wiped them out, could not be traced.

In the same cage as Martha, the last remaining passenger pigeon; went Incas, a captive died after his mate. So many lasts.

Shift thinks about captivity. About being a migratory creature confined to one place. The sun seems to slip out of reach with winter, and it is hard for Shift and Mikhail to find enough food to survive. They think about themself, and about Mikhail, and Mikhail’s favorite brother, who he tells them about one afternoon when the snow sheets down like a soft blanket, twisting its way into the hollow opening of their cave.

“The child is odd, you know? And what can you do about it,” Mikhail says. “My mother explained it to me that way. About changelings, creatures that were just different and living here. Some try to kill it in hopes they’ll get back what they had. Others will trick it away, and they’ll have nothing. Some few notice and raise the child as their own, and gain good luck. But one day, someone will come by and the child will say ‘look, there’s my parents’; jump over the fence and walk away. That’s what my eldest brother did. He did it to gain a title and a position that saved the lives of my other brothers, gleaming medals and honors that two years later meant nothing. He was a hero for two days and a traitor the rest.”

“Are you angry at him?” Shift says.

“How can I be?” Mikhail says. “He saved us. How can I be. Even if I want to?”

Shift thinks about kinship as they sew the memory of Mikhail’s brother, his hard practicality and his oddness, into their chest with a blanket stitch up the curve of their ribs. Their needle slips through flesh leaving pinpricks of blood behind, and Shift thinks about how lately, every push of the needle hurts more. They think about their skin growing around them, working on its own like the machine it is, despite their own efforts, and wonders where the spark of their own self has hidden. Everything they sense seems dulled.

“Four more years,” Shift says, as they pull their red sweater close. Mikhail takes their hands and rubs them until their fingers warm and uncurl.

“Do you think we’ll live to see the end of the world?” he says.

“What’s the end of the world?” Shift whispers.

***

The difference between watching twelve more years of everything vanish and living four more years moment by moment is the difference between flying above the sea and drowning in it.

The Mohoidae family is dead. Feeding on nectar, the small songbirds are black and yellow, brown and spotted white.

The Oloma’o hasn’t been seen in years, since the mosquitos on the islands.

The black-lored waxbill lived within two thousand kilometers, and didn’t go extinct as much as was not sighted again.

The po’o-uli, with its black head and body of silvery-grey, was smaller than a hand. Because of mosquito-borne disease, they were forced upward, because they lost food, because of pigs and mongooses, cats and rats.

Shift is not fond of cats, rats, and dogs; just the way they are not fond of humans. But they do not have to be a cat, a dog, or even a mosquito. Instead, they are a human, with black hair the perfect color for feathers and snow-shadow eyes. They like the look on them much less than on Mikhail, who, when he sings in front of the fire late in the evening, seems as unconquerable as a bird’s glance, with strong arms and a back meant for holding. If they could give Mikhail wings, Shift thinks, then both of them could ascend into the white sky and leave the world behind. Shift could show Mikhail the halls of the infinite, and introduce him to their section of Noticing with its perfect records, so unlike the messy stories and tales told from Mikhail’s sweet mouth.

But Mikhail has no wings, and the spark within him can’t be dragged free of his body. Mikhail is a Man, and his species will be extinct in four years. Perhaps this cave is Shift’s own zoological space, where they can watch him exist while everything of his kind in the wild shrivels and dies. Perhaps they will be the last together, undocumented and alone, and will slip into extinction quietly, without being Noticed at all.

And perhaps, Shift thinks, that is important too. There will not be tales told, there will not be taxonomies, but there will always be this: some kind of mystery in the heart.

***

(a national indie excellence awards finalist!)